A History of Interest Rates Fourth Edition by Sydney Homer and Richard Sylla

A History of Interest Rates Fourth Edition by Sydney Homer and Richard Sylla

A History of Interest Rates Fourth Edition by Sydney Homer and Richard Sylla

A History of Interest Rates Fourth Edition by Sydney Homer and Richard Sylla

Homer and Sylla treat each century and country independently, causing disconnected understanding as interest rates gauge the availability of credit and the availability of investment alternatives. TheBirthOfTheModern contrasts events across a time period and would have perhaps been a better narrative model.

Our earth is degenerate in these latter days; bribery and corruption are common; children no longer obey their parents; every man wants to write a book, and the end of the world is evidently approaching.

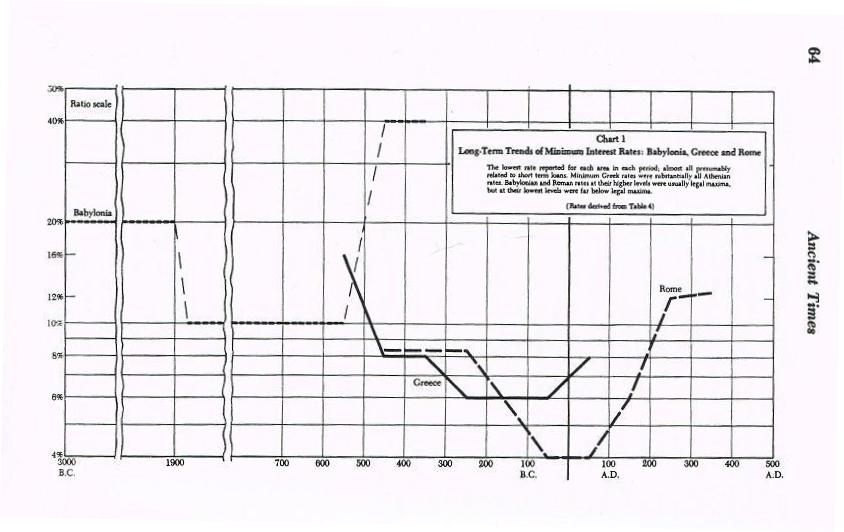

"Of all kinds of capital," said Demosthenes, "the most productive in business is confidence, and if you do not know that you do not know anything." Phormio, an ex-slave turned banker, became the richest man in Athens. By the third century BC, Greek finance was highly developed and the use of credit was general. By 200 BC the real estate loan, once dreaded, came to be regarded as a convenient means of procuring money at a moderate rate, especially by the small farmer.

Cato said: "In preference to farming one might seek gain by commerce on the sease, were it not so perilous, and in money lending, if it were honorable ... How much worse the money lender was considered by our forefathers than the thief...." Nevertheless, Plutarch says that Cato himself invested in mercantile loans, probably secretly.

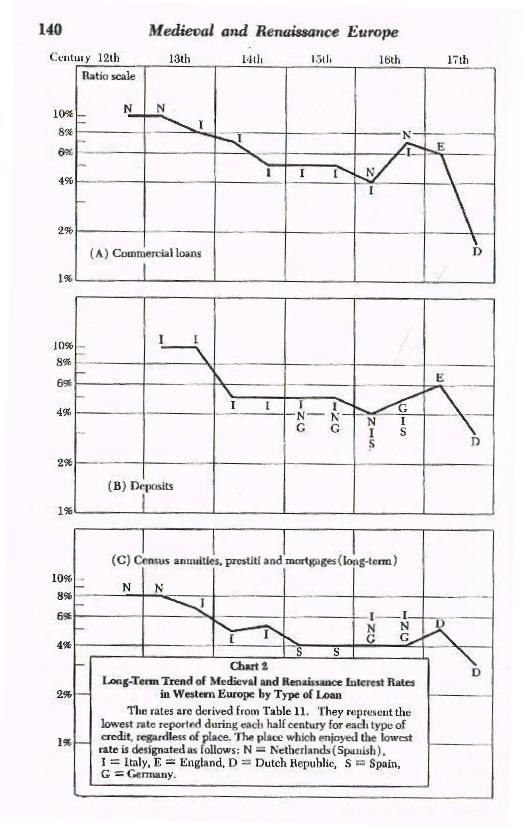

In fourteenth-century Barcelona, the rate of credit expansion by the banks was estimated at 3 1/2 times the specie reserve; in Bruges, the specie reserve ws typically 29% of deposits. The assets of the banks were probably devoted largely to investments rather than to loans...

Charlemagne was the first prince to forbid all usury."I'm the king, you're poor. That's just the way it's supposed to be."

Credit gradually became a political device and has remained so ever since: an essential weapon of politics and of national defense or offense. The princes, however rarely managed to develop efficient state credit. Something like modern methods of state finance were developed only by the northern free towns and by the Italian republics; these methods were later adopted by Holland and England. The consent of the propertied public was the essential ingredient. The ultimate triumph of more democratic governments throughout much of northern Europe was probably due in part to the ability of these governments to mobilize their enormous public resources.

California, as usual, set some records which are hard to duplicate elsewhere. The transition from Mexican to American ownership was complicated by the economic effects of the gold rush. After 1849 the price of California cattle multiplied and then collapsed. The Mexican owners of the great cattle ranches of southern California found themselves fabulously wealthy, borrowed freely by mortgaging their ranches, and with the collapse they generally lost their ranches. The lenders were often French, Swiss, German, and Yankee speculators.

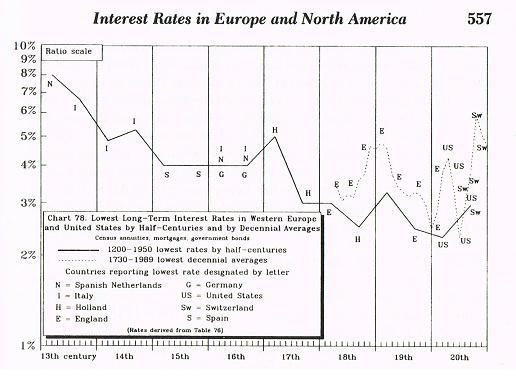

For this history, one event in the long-term market stands out: at the peak of yields in the fall of 1981, the US government borrowed money for twenty years by issuing 15 3/4 % bonds, which sold at just under par to yield 15.78%. This stands as the highest bond yield the government had to pay in the two-century history of the republic.( one hand did not talk to the other )

The investment markets were tightly controlled, and interest rates were not allowed to rise as they had risen in World War I. Instead of paying 4 1/2 - 5% interest for war loans as in 1915-1917, England now fought a 3% war.

The ownership of land was preferred to commerce even when the rate of return on capital invested in land was far below the rate of return on capital invested in trade and in money lending. Social opinion and government policy were unfavorable to the merchants and bankers, who in early times were considered malicious and were heavily taxed.

The oldest credit institution in China was probably the monastery pawnshop. In AD 200-300, Buddhist monasteries, like Babylonian, Greek, and Roman temples, practiced pawnbroking. They extended credit to rich and poor against precious metals, farm produce, and a wide variety of articles, which they held in warehouses. Private pawnshops were reported as early as AD 800, and by 1500, they had supplanted the monasteries.

The regular flow of funds from savers to investors through the medium of securities or of institutions apparently never began. Chinese credit continued over the centuries to consist almost entirely of consumption loans made by individuals to individuals.